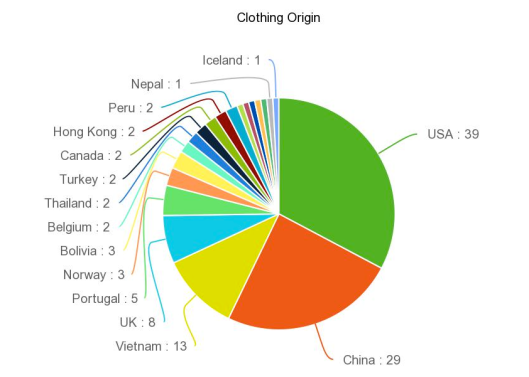

We’ve just passed the 2-year anniversary of the collapse of Rana Plaza, the site of the clothing factory in Bangladesh where 1,133 garment makers were killed. On my Twitter feed, the Fashion Revolution Day hashtag was trending last week, asking #WhoMadeMyClothes? This question has been on my mind for some time, hence the deeply flawed pie chart above, which attempts to show where all my clothes and shoes come from. (More about that chart in a bit.)

We’ve just passed the 2-year anniversary of the collapse of Rana Plaza, the site of the clothing factory in Bangladesh where 1,133 garment makers were killed. On my Twitter feed, the Fashion Revolution Day hashtag was trending last week, asking #WhoMadeMyClothes? This question has been on my mind for some time, hence the deeply flawed pie chart above, which attempts to show where all my clothes and shoes come from. (More about that chart in a bit.)

It’s not that we don’t know there’s a problem with our overconsumption of cheap clothes. Books like Elizabeth Cline’s Overdressed decry the human and environmental costs of fast fashion, and we have only to look inside our closets to see that many of us own far more clothing than we can ever use, much of it produced by economically precarious workers who lack fair wages and safe working conditions.

I don’t want my wardrobe or anyone else’s to become a source of anxiety or consumerist shame, but I also don’t want to be participating in a system that exploits laborers in countries like Bangladesh, where many garment workers continue to lack adequate protections. So what can we do?

If we’re buying new clothes, it doesn’t always help to be guided by the origin tag on the label. In Deluxe: How Luxury Lost Its Luster, author Dana Thomas explains that the label on a fancy Louis Vuitton handbag can sometimes proclaim “Made in Italy” even if the handbag was mostly produced by underpaid teenagers ten thousand miles from Rome. So the labels alone tell us very little.

I made a pie chart of all my clothes and shoes, but it’s not clear from the country of origin how my wardrobe measures up in terms of fair wages, working conditions, or sustainability. (A handful of country labels didn’t fit into the chart, but they are India, Morocco, Bulgaria, Italy, and Sri Lanka, each containing one clothing item.)

The USA section of my chart includes a number of handknit sweaters, and I happen to know they were humanely crafted in USA because I knitted them myself. But the origin of the yarn is another story. The yarn for my Malabrigo sweater was spun in Uruguay. The yarn for my Madeline Tosh cardigan is Peruvian, as is the fiber for my Juniper Moon sweater. My Tahki sweater is 30% French Angora, but there’s no word on where the other 70% of the yarn came from. I knitted two sweaters using Dream in Color merino, and their website simply says they’re “dedicated to using domestic fibers and mills whenever possible.” Whatever that means. But at least I’m sure the woman who knitted those sweaters wasn’t being exploited, so there is that.

Beyond the problem of worker protections is that of the environment. Major clothing brands like Patagonia assert their commitment to sustainable fashion, but how much of that is greenwashing? Publicly traded companies need to grow, and growth inevitably results in waste. The textile industry produces millions of tons of discarded fabric per year, clogging our landfills with polyester. We’re also using up water. Every time we buy a new cotton T-shirt, we’re consuming over 700 gallons of water. The water footprint is embedded right into the fabric.

We could swear off buying any new clothes, but that approach tends to favor those who already possess a lot of privilege. I’m aware that I’m mostly able to wear whatever I want, in part because I’m an average-sized white woman with a PhD, working in a creative field. If I choose to wear a skirt hand-crafted from recycled T-shirts, I’ll hardly lose much credibility. But many people feel they need to wear up-to-date and brand name clothing in order to look professional. It’s said that clothing makes the man, and this is especially true for members of less privileged groups, for whom designer clothing and accessories may help to signal middle-class status, professionalism, and the right to belong.

Perhaps our problems can be solved in a second-hand store. I’m never going to give up buying new shoes, mainly because my arches have certain needs, but I’m a big fan of vintage and an even bigger fan of thrift shops. It’s true that the second-hand clothing industry has its own problems, and we do need to think twice before we haul a load of unwanted clothes to Goodwill. But shopping at thrift stores is at least better for the environment than feeding the fast fashion machine at the mall. Critics will say that we aren’t doing much for the economy when we buy second hand, and I don’t really have a good answer for that, but there are no perfect solutions.

So, who made my clothes? For the most part, a lot of people from around the world, working in difficult conditions in an industry that doesn’t pay very well. I want to change that, one purchase at a time.

In his essay “The Nature of the Gothic,” Victorian art critic John Ruskin argued that the problem of dehumanizing mass production can’t be met by simply preaching about what’s right. “It can only be met by a right understanding, on the part of all classes, of what kinds of labour are good for men, raising them, and making them happy; by a determined sacrifice of such convenience, or beauty, or cheapness as is to be got only by the degradation of the workman; and by equally determined demand for the products and results of healthy and ennobling labour.”

In other words, as much as possible we need to sacrifice what’s pretty and cheap and convenient if it degrades others, and we need to demand what’s healthy and ennobling. Ruskin wrote that over a hundred years ago, but it still sounds good to me.