My beloved mentor Michael Levy passed away on Monday. I’m struggling to find words to express how much he meant to me. He was the best and kindest of men, and I loved him dearly.

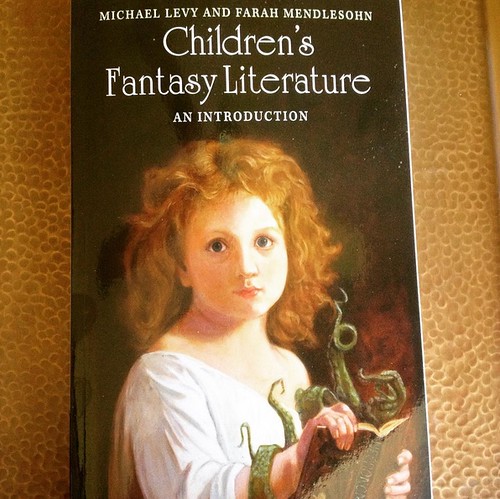

Below is my review of Mike’s book with Farah Mendlesohn, Children’s Fantasy Literature.

An engaging narrative history, Children’s Fantasy Literature (2016) illuminates and contextualizes the English-language tradition of children’s fantasy. Keep a notebook handy as you read this fascinating study, because you’ll want to head to the library when you’re done.

Authors Michael Levy and Farah Mendlesohn draw upon a range of critical traditions to classify children’s fantasy, distinguishing Tolkien-like high fantasy, for example, from what Brian Attebery calls the “indigenous fantasy” of everyday life. The authors frequently reference the categories of the fantastic (immersive, portal-quest, intrusive, and liminal) that Mendlesohn describes in her acclaimed study Rhetorics of Fantasy (2008). As the authors show, children’s fantasy literature runs the gamut from self-contained magical worlds to journeys through portals into magical realms. But children’s fantasy also includes stories in which magic intrudes suddenly into ordinary life, as well as indefinable flirtations with the surreal.

An impressive number of books are discussed in this study. Rather than focus solely on the greatest hits of the field, the authors have chosen individual works for their significance to the narrative trajectory. Thus you’ll find the usual warhorses—J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, J.K. Rowling, and Ursula Le Guin—but also such lesser-known authors as Franny Billingsley, Nnedi Okorafor, and Hiromi Goto.

Levy and Mendlesohn use a textile metaphor to describe their approach, broadly covering the overall fabric of the field in early chapters, while tracing individual “strands in the weave” as they move chronologically toward the densely populated present.

What the authors are doing in this book is showing us how children’s literature has been shaped by the changing role of children in society, by historical shifts in values, and by the legacy of groundbreaking texts. In their own words, they have “traced changing ideas about who children are and how they grow to adulthood . . . [examining] the ways in which this evolution has shaped the genre of children’s literature.”

It goes without saying that as the experience of childhood has changed, so have children’s books. But Levy and Mendlesohn are able to illustrate this vividly. For example, they demonstrate how the disruptions of British childhood during and after WWII fostered a preoccupation with evil, agency, and consequences in the work of C.S. Lewis (The Chronicles of Narnia) and Susan Cooper (The Dark is Rising).

Along with C.S. Lewis, Diana Wynne Jones is the most thoroughly discussed author in this text, in part because her work is so wide-ranging and impinges upon so many different threads in the tradition. Her book Fire and Hemlock is discussed in a section on “A sudden flowering of heroines”—which also includes Patricia McKillip’s The Forgotten Beasts of Eld and Robin McKinley’s The Hero and the Crown.

A few other highlights in this study are Ursula Le Guin’s “rejection and reworking of Tolkien,” the questioning of “destiny” as a narrative construct, the decolonization of the imagination, and the increasingly visible role of LGBT writers and authors of color.

For this reader, the most fascinating chapter in Children’s Fantasy Literature is the final one. Addressing the “bitterness” of contemporary Young Adult fantasy, Levy and Mendlesohn show how far we have come from “consolatory” or escapist fantasies. In David Almond’s Skellig, readers encounter a fallen angel and a boy whose little sister is critically ill. Philip Pullman’s The Dark Materials trilogy takes young readers on a brutal journey with few consolations. Writing for increasingly sophisticated teen readers, Margo Lanagan (Tender Morsels) references loss and isolation and sexual abuse, while Suzanne Collin’s The Hunger Games describes a world of inescapable violence and injustice. In reading these books, young readers are struggling to “find their own lives and gain agency in the world they live in.” Childhood is more difficult than adults remember, and the bitter fantasies of the current age allow children and teens to see their experience reflected in a truthful way, without coddling or deception.

To read this valuable study is to have a seat at the table while two of our most insightful scholars share their passion for children’s fantasy literature. Farah Mendlesohn is one of our most brilliant critics, and Michael Levy was a giant in the field of fantasy scholarship, a generous mentor, and an inspiration to a generation of scholars. This book is highly recommended.