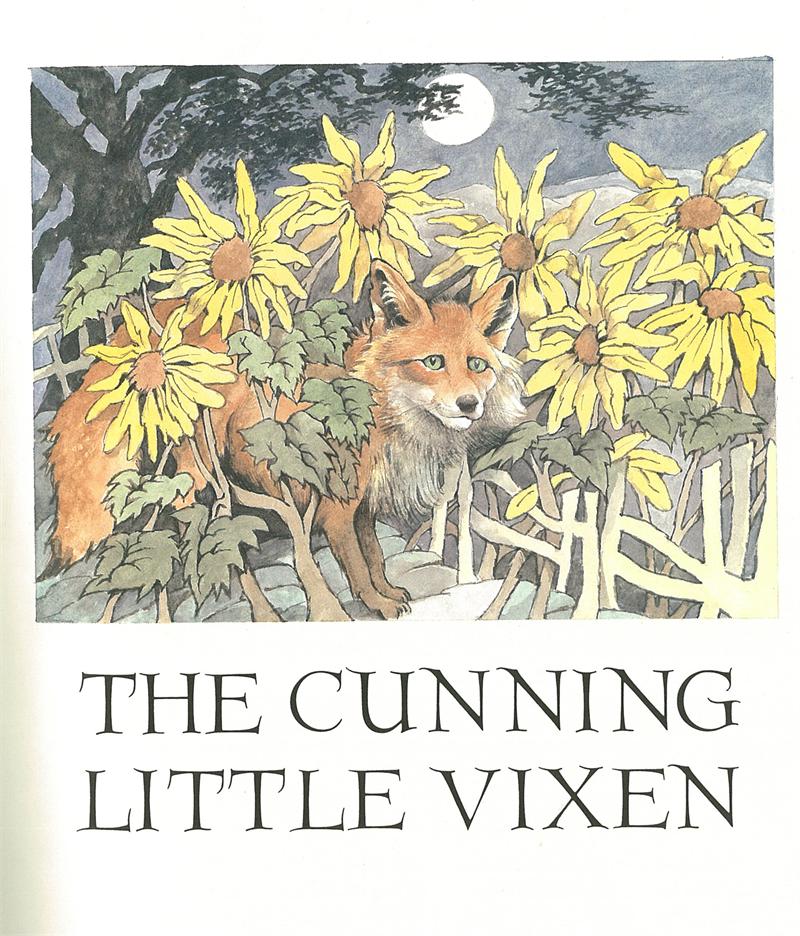

I mentioned a recent vulpine obsession; as a result, my readers may have to endure a few fox-themed posts. We’ll begin with Leos Janáček’s masterpiece, The Cunning Little Vixen.

As an opera, The Cunning Little Vixen is extremely difficult to stage. (So I’m told. I’ve never actually produced an opera.) The New York Times, for example, claims the work has a “nightmarish reputation among opera companies.” Following the U.S. premiere in 1924, “Vixen” wasn’t staged professionally in the States until 1975, when the Santa Fe Opera gave it a go. One of the opera’s difficulties lies in its extensive, glorious orchestral interludes in which the vocalists have no lines to sing. And then there’s the matter of singing animals and insects interacting with humans. That requires imaginative staging, to say the least.

Quick opera summary: a resilient fox cub is captured and raised by a forester, escapes and finds true love and raises a family, then is shot and killed by an evil poacher. The forester, meanwhile, reflects on the circle of life and the connection between humanity and nature.

In December I had dinner with a friend who performs with the Cleveland Orchestra, and she told me about the innovative approach that Cleveland took with the opera a few years ago, which involved vocalists interacting with an animated screen. The BBC has also produced an animated film version, directed by Geoff Dunbar, musical direction by Kent Nagano. More about that in a moment.

Animating an opera is never a bad idea, and in the case of The Cunning Little Vixen, or Příhody Lišky Bystroušky (The Adventures of Vixen Sharp-Ears) such an approach is entirely appropriate, since Janáček based his opera on a 1920’s newspaper comic strip by Czech artist Stanislav Lolek and the subsequent novelization of Lolek’s work by Rudolf Těsnohlídek.

I recently reread Těsnohlídek’s story of Vixen Sharp-Ears (the 1980’s English translation with all the beautiful illustrations by Maurice Sendak) and I was struck by the fact that it was Janáček, not Těsnohlídek, who introduced the vixen’s death as a tragic plot element. Těsnohlídek certainly hinted that the vixen’s days of freedom might be numbered in the future, but he didn’t let the damn poacher get her. (Těsnohlídek, incidentally, has absolutely the saddest life story of any writer in history.)

In Nagano and Dunbar’s animated production of the opera, the bold, freedom-loving Sharp-Ears may not survive, but she does insinuate her way into the audience’s collective heart.

Below, a few screencaps from my DVD. This isn’t the best production of “Vixen” ever–try this one directed by Sir Charles Mackerras for superb orchestral direction and singing–but I love it anyway. It’s in English! It has cartoon foxes! My favorite scenes include Sharp-Ears dreaming about her mother when she’s tied up in the forester’s yard; Sharp-Ears falling in love with a dashing fox (played here by a tenor, not the usual mezzo); and of course the forester’s exquisite reverie at the end, as his own life draws to a close.